AVPA monthly blog

Iain Corby, Executive Director AVPA

As the tech sector awaits the somewhat overdue government response to its consultation on the Online Harms White Paper, two important previews of its thinking were published last week.

The first was the VoCO (Verification of Children Online) Phase 2 report. This child online safety research project was undertaken jointly by DCMS, GCHQ and the Home Office and responds to the challenge of knowing which online users are children. The project has brought together children, industry and child safety stakeholders to consider the technical, commercial, legal and behavioral factors that would enable companies to recognise and better protect their child users.

- The process of recognising child users was, however, considered to be a complex ask. Platforms recognised the value of taking a risk-based approach to age assurance. Such an approach would require companies to assess the likelihood of children accessing their platform and the severity of risk posed to them, selecting an age assurance method that delivered the confidence that fitted this risk profile. For example, a site that contains age restricted products or services such as online gambling would want to have a high level of confidence about the accuracy of which of their users are under 18. This site may choose an age verification approach to deliver this.

This is a welcome conclusion. As a sector, we are not advocating for age verification to be applied whenever some form of age assurance is merited – only when the level of risk justifies a more rigorous check. However, determining when this applies was highlighted by the report as problematic:

- Industry stressed that currently, they did not feel they had the detailed information needed to be able to make these assessments and implement age assurance effectively and with confidence. There is no consistent approach to defining risk across platforms or for establishing the corresponding level of confidence needed from an age assurance measure.

We sympathise with this dilemma. A simple first step would be to adopt a common language around the levels of confidence under discussion. The BSI standard PAS1296:2018 already provides a solid basis for this, and DCMS recently agreed to sponsor an update to that document which will make it even easier to use as a point of reference for differing levels of assurance. This will then facilitate conversations between regulators and industry, and within the industry, about the appropriate levels to apply to different circumstances.

- The project ran a technical trial that aimed to scale age assurance while preserving data protection. The benefit of such an approach being that multiple stakeholders across different parts of the digital ecosystem can age assure a user with the same information, reducing friction for users and the sharing of personal data. This means that if a child has had their age band established once, this could enable age assurance across multiple platforms without parents needing to repeatedly consent to the further sharing of data. A trial of this process was run as part of Phase 2 and found that it was a viable approach. Further trials are recommended and greater work needed to explore how trust between the participants can be assured at scale, through a structure like a Trust Framework or a similar approach.

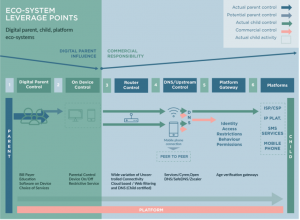

This is a natural extension of the work the AVPA is already doing to create a trust framework and interoperability across its members for age verification. In the pilot staged by VoCo, controls were applied either by broadband suppliers or by parents at the device level, with parents alerted when their children sought to use new applications:

- The solution is easily accessible to broadband customers and the trigger to get a digital parent to go through the process is initiated when a child wants to access, for example, an app. Here, the digital parent and child use their own devices and do not require significant education or support to complete the user journey. For this trial the age check provider partnered with a global Internet Service Provider (ISP) and a third-party app provider

- The assessment of the child’s age occurs during a home router set-up. This technical trial demonstrated that a parent-initiated user journey where a parent, setting up a home router can identify which devices on the network belong to children and adults, for example, a child’s mobile device. Following this the digital parent can respond to a request from their child to access the app. For this trial the age assurance provider partnered with a cybersecurity company focusing on parental controls, device management, privacy and threat analytics

The trials did not involve the platforms, which we believe is an essential element of the full range of protections that will be needed to protect children. Public WiFi access, new devices, and of course devices in households where parents are either unaware of or unwilling to apply controls all need to be addressed in any comprehensive systemic approach to child protection.

Also issued last week was the Government Response to ICSAA (the Independent inquiry into child sexual abuse). This reiterated policy announcements from the interim response to the White Paper. For example:

- The Government has been clear that we expect companies to use a range of tools now to protect children online and that we expect that age assurance methods, including age verification, will play a key role in the online harms regulatory framework.

The term expect does not suggest that age assurance, let alone age verification will be a legal requirement. Perhaps we are in the territory of ‘nudge theory’. With pornographic websites facing losses measured in millions if they implement AV and their competitors do not, it is hard to have confidence that nudging will work.

- The VoCO project showed that there are a range of age assurance methods, supported by different data sources, that companies can use to assess the age of their users. Different age assurance methods provide differing levels of confidence in the age of the child. Age verification is one type of age assurance measure and provides the highest level of confidence in the assessed age of the child. Current age verification measures are effectively a full identity check.

This is broadly correct, but the final sentence is unfortunately phrased. Age verification can be achieved with a high level of confidence without knowing identity, for example, through facial analysis, where a sufficient buffer is set between the age assured and the age estimated. Also, what this sentence disguises is the fact that even where identity may be used to prove age originally, it need not be retained or shared when a user needs to provide verification of their age after that initial check has been completed.

These two documents bring into stark relief the urgent challenge facing policymakers around the world, but particularly in the UK. Multiple pieces of legislation, new and existing, are demanding that organisations know the age of their online users, and where required, secure parental consent, but the infrastructure is not yet in place to facilitate that. The EU is commissioning a solution to be trialed across at least four Member States that will drive this forward, and the UK would be well advised to watch that closely. Meanwhile, AVPA members stand ready to help address these problems and indeed can already do so if there is sufficient support from government and regulators to enable putative answers to be rolled out swiftly.